Petrified

As in Forest. As in “The Petrified”, like our friend, Karl Larson, calls The Petrified Forest National Monument near his home in Showlow, AZ. Here it’s called El Parque Nacional Bosques Petrificados.

We’d made the call to pick one coastal city before we left north and west to Chile. The historical Atlantic port Puerto Deseado was selected, mainly because it is way off the main highway and because the Bosque Petrificado was halfway between. The guide book called the city “charming”. We also needed a welder to repair our truck and a fishing port has welders.

More long sections of empty road, more semis, more guanacos, more rheas, a left turn off the highway and, suddenly, a new animal.

The Patagonian Mare is a rodent, rabbit-like animal that looks like a cross between a jack rabbit and a lap dog. Yet another, specialized animal specie making a living in this harsh environment.

The Bosque Petrificado was a forest of a species of pine that lived in the Jurassic period of the earth about 150 million years ago.

The trees stood up to 100 meters tall and four meters in diameter.

They lived up to 1000 years old until a cataclysmic blast from a volcano blew them down and covered them with ash.

The trees, sealed within the blanket of ash, slowly replaced their organic matter with minerals that leached through the soil.

Over the course of millions of years, the trees came to be petrified trees: rocks that resemble trees.

This particular section of the forest became exposed from erosion. It was formed into a National Park in the early 1950s.

The only accommodations to be had within 50 km of the Petrificados was either a gas station/motel 50 km away on the highway or a campground called Estancia Las Palomas 12 km from the highway and 12 km away from the park entrance on a dirt road. We took the campground.

We arrived to the campground to find a very surprised host named Nicolas. Nicolas quickly changed his look of surprise to a broad smile. When I asked Nicolas if they were accepting campers, he explained to me, in rapid Spanish and flourishing gestures, that they weren’t open, but they were open, and to make ourselves comfortable. Everything was “tranquillo” (tranquil, which translates into “chill” or “mellow”) because he and his wife ‘were entertaining family for New Year’s, an important Argentine holiday’.

Well, then: thanks, Nicolas. Chill it would be. We parked the camper next to the campground store to cut the wind and raised the roof.

From the camper we could see, through the windows, boxed wine on the shelves of the campground store. We were on our last half-bottle; it was New Year’s Day. We were unable to buy groceries or wine at the last town. Everything closed. We were in dire straits.

In time, Nicolas came whistling-by, keys-a-jangling to get something from the store for his family party. I sprung. Nicolas, may I please buy a box of wine? (It didn’t sound that smooth in Spanish, but Nicolas got the point). ‘Of course’, Nicolas replied, and grabbed a box off the shelf, then he hesitated. ‘This isn’t very good wine’, he said, ‘would you like something better?’ This guy’s an angel, I thought. ’Yes, please’, I said.

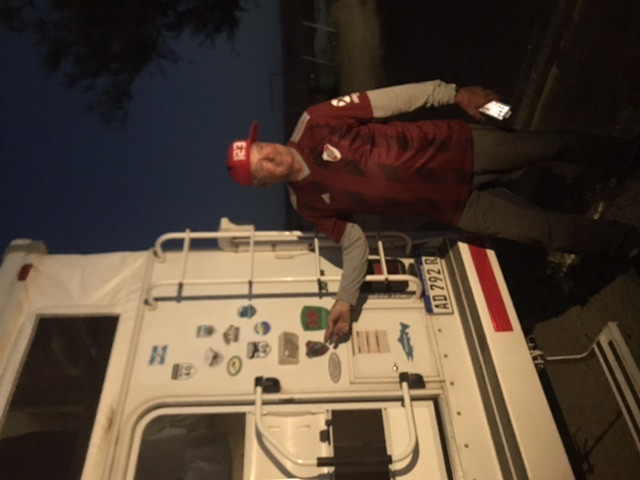

As Nicolas was turning to go to the house, he noticed the Rio Plata soccer team sticker on our camper. He then asked how we, people from Alaska came to be fans of that soccer team. He said his sons were crazy about the team. I explained the sticker was a crank gift from friends we’ve met in Mendoza.

While we were in Mendoza with our new friends, Jorge and Fabiana (see earlier story), one of the last things Jorge did was to plant that sticker on our camper.

Rio Plata is one of the two teams of a great rivalry in Argentine soccer. The sticker has raised conversation and reaction all across Argentina. The most memorable was upon our return to Argentina from Chile early December.

The head of the Argentine Aduana (customs) at the Futaleufu border crossing had just finished chewing me-out for taking our Argentine-registered vehicle out of Argentina. As a non-resident, I could not take my vehicle out of Argentina (huh?). He then, talking in rapid Spanish and escorted by two soldiers in olive-drab fatigues, accompanied us out to the truck. He demanded we open the door to the camper. Shit. Here it comes: a complete, U.S. Customs-style tossing of the campers contents and a thorough search. I could envision ourselves sitting right there, bolting things back together for days. “Que Lindo!” (How beautiful!) he said as the door swung open, his face twisting from a pinch to that of an excited boy. “I have a camper, too, a Renault! I like this fold-down step!” That was it.

As we closed the door he noticed the Rio Plata sticker. He, too, was surprised to see that sticker on the back of a gringo vehicle. The soldiers and he began, with vigorous head nodding and shaking, a brisk debate on which soccer team they liked. I grabbed my camera and put them to a thumbs-up or thumbs-down vote. The soldiers, who’d been keeping a stoic composure heretofore, lost it, and began snorting and laughing. This is one of my favorite photos of the trip. I tell people we were allowed back into Argentina by a margin of two votes to one.

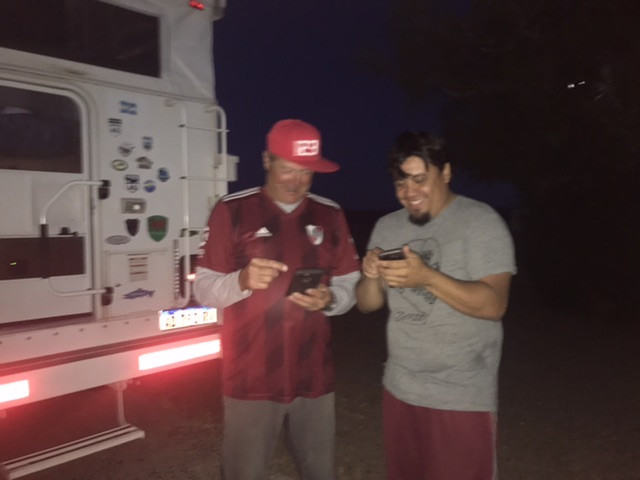

Meanwhile, back at Estancia Las Palomas, Nicolas goes to his house and returns with a bottle of wine, along with his son, son-in-law and grandson in tow. His son carried a Rio Plata team jersey and a Rio Plata hat. Very excitedly, he asks me to put on the jersey and hat. He next typed on my phone a Spanish phrase which he wanted me to say on video.

I’ll do anything for wine. I don the regalia, memorize the phrase (which was roughly “bring your big mouth to Madrid”) and we rolled his camera. I added a Spanish expletive and a physical gesture considered rude in this part of the world, both things we’d learned earlier in the trip, which put them on their knees laughing.

The Mission of Road Trip Patagonia is to connect Alaska with Patagonia. Mission accomplished that day.