The River of Dreams

That is what was inscribed on the dry bags tied to the horse panniers. A two hour drive from Coyhaique found us at a trail head with eight horses being prepared by a pair of huasos (cowboys) and the staff packing goods for shipment into the camp.

We were told we had a two hour horse ride to the river and another hour boat ride to the camp.Looking at the elevation of the trail ahead all we could see was steep incline as the trail disappeared into the trees.

There are classic western movies, such as El Dorado, where adventurers seeking gold are led by an Indian guide through steep canyons with narrow defiles to find the mythical treasure they seek. It seemed we were on such a quest and the treasure was trout.

Our guide was a huaso named Jorge. Jorge ran from horse to horse energetically packing them, loading them and cinching them with a smile on his face.

Eduardo, our host at Magic Waters Patagonia lodge, had told the story of how he was interested in fishing the Rio Blanco Canyon which was our destination for this day. The Rio Blanco, Eduardo explained, was within the walls of a steep Canyon, and access from upstream or downstream was blocked by a series of waterfalls on either end. The only way in was by either helicopter or pack train. While Eduardo was scheming a way to get into the Canyon Jorge, the huaso, was scheming a way to make a better living for himself.

Jorge was born and raised in the Canyon, and he was finding raising beef cattle there to be difficult; the forest in the Canyon is mature and thick. The valley floor is narrow to nonexistent. The river is wide and fast. The high mountains limit the sunlight and the coastal weather brings disproportionate overcast & 70 inches of annual rain. Grass grows slowly. The only two paths into the canyon were one along a steep, narrow trail and second trail that was steeper and narrower. Cattle was proving a poor return in Jorge’s beloved Rio Blanco Valley, but he’d heard tourism was growing in the surrounding area. Maybe, he thought, fisherman would come to the Blanco.

Jorge made a few telephone calls and, through process of finding likely prospects, reached Eduardo. Eduardo, stunned by the serendipitous nature of the call, made arrangements to have Jorge guide him into the canyon. Eduardo caught the hell out of fish. With Jorge’s help he found a piece of land there, purchased it, and set up the camp. Jorge would be responsible for logistics and caretaking the camp. Jorge, the entrepreneurial huaso, had identified a market, created a world for himself to fulfill a need then inserted himself into it.

In a past life I’d owned three horses, but I had never done anything like this before. The two hour ride into the canyon was worth the entire trip. Jorge’s sure-footed horses knew the trail, which was alternately (or at once) narrow, muddy, rocky, steep up, steep down and in places bolstered with logs. Comanche, the horse I’ve been given, had a penchant for avoiding the mud by walking the very edges of the trail, be it the extreme inside or outside edge. As Comanche slowly and confidently placed hoof before hoof on the trails edge I could hear the river, mostly unseen through the thick brush and bamboo, roaring through the cataracts below us.

There was no opportunity to pull a camera on this two hour ride due to the intense concentration required to keep one’s balance or ones head from being clipped in the brush as Comanche passed close to the inside edge of the trail. After what seemed an eternity of living moment-to-moment, we broke-out of the brush and onto a grassy clearing where we saw the pontoon rafts tied to the bank. This would be where we traded horse for boat. Comanche celebrated by breaking into a gallop, which I quickly reigned-in. I was exhausted, and in no mood to further expand my equestrian horizons.

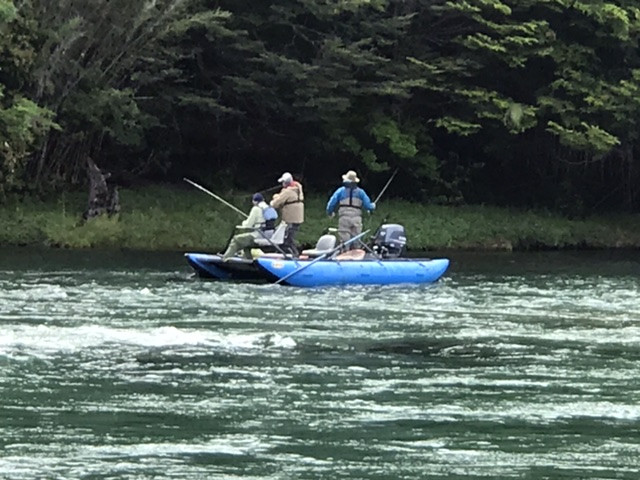

The rafts, which are a catamaran style of construction, were powered by Yamaha outboard motors with a jet pump for propulsion. We use these in Alaska almost exclusively, and I couldn’t resist snapping a photo of Jorge, the Chilean huaso, doing an Alaskan guide chore of applying grease to the shaft bearing of the jet pump.

Monte, our guide, drove us upriver while Jorge drove Thomas, the camp hand, and Fernando, the chef, along with a pile of kitchen supplies. It was slow going. The “catarafts”, which are normally designed for three persons and a light load, were heavily weighted-down. The current we faced was substantial. Monty carefully maneuvered the watercraft from the inside of each bend to the next inside bend to avoid the strongest currents as we plowed our way upstream and, after an hour and a half, we arrived to the camp.

While the camp had not been attended since the last Chilean autumn, it was in perfect condition. I remarked how if, in Alaska, we’d left one of our camps in this condition it would be shredded by bears the following spring Monte remarked cattle would do the same thing by rubbing if left to their own ways. It was Jorge’s job to keep them out.

Everything for this camp had to be brought in either swung under a helicopter or strapped to the back of a horse. I amused myself constantly by looking at the equipment and wondering how it got there. Most of the lumber for the camp was cut from trees along the river and left standing to dry before being used for construction.

There were three roomy tents for guests, a couple of staff tents, a bathroom & shower building with hot & cold running water and a huge kitchen & lodge tent.

The gable supports for the tents were handcrafted in a jig, disassembled and brought to the camp on horseback. The custom-made tent covers were created in Coyhaique. All the tents had electricity due to a solar generating system as well as a gasoline generator as back up. The tents had fuel oil heaters. The lodge tent had a big enameled classic wood stove and oven.

It was all perfect. In the evening we sipped wine and watched the shadows move. At night, as we slept, all we could hear was the wind and the river and if we went outside we could see a narrow band of stars above us. It was quite an ideal experience just to be there among the old growth Chilean forest and the remarkable bird life.

We fished by walking a few side channels of the river, but mainly we drifted as Monte rowed & we cast towards rock walls, eddies and the unbelievable amount of fallen wood structure along the river banks. The action was almost nonstop as brown trout rushed out of nooks and crannies to nail our flies.

Browns being Browns, larger fish would be present one day and gone the next.

After seeing a couple larger browns rush out and attempt to eat small fish we had on our line, Monte put on a gigantic articulating streamer which drove the fish crazy. One time we watched two 20-inch-plus fish competing to eat my fly The winner inhaled the fly and was given a reprieve when the stinger hook broke off from the fly. Often, the fly would slap the water and we’d see a Brown jet-up vertical from unseen depths to hit it. It was nuts.

We saw all 20 miles of the river valley. We even went as far as we could upstream to the edge of the upper canyon rapids and caught fish there.

Magic Waters Patagonia remote camp was an amazing experience. I write this as we are parked in a campground near the city of Esquel, Argentina. The sounds of civilization are all around us. We wish we were there, in Rio Blanco canyon, now.