Dashboard Saints

While growing up in Alamosa, Colorado, Lynnette’s Hispanic friends had a plastic Jesus on the dashboard of their truck. My grandmother had plastic Virgin Mary on her 1961 Falcon. My father kept the same Saint Christopher medal on the dash of every vehicle he owned from 1945-on. Our friend Karl has a plastic Moses, a prize possession found in mint condition while scrounging a swap meet, displayed in impudent irony on the dash of his 1990 Nissan truck. He claims it parts traffic.

During our 1984 road trip Rick and I glued an olive-drab plastic soldier, Sergeant Rock, to the dash of our VW Bus. Sergeant Rock held a rifle mid-grip in one hand. The arm of his other hand curved upward & arched forward in a wave as he looked back, exhorting his troops forward into the unknown (through a hail of bullets).

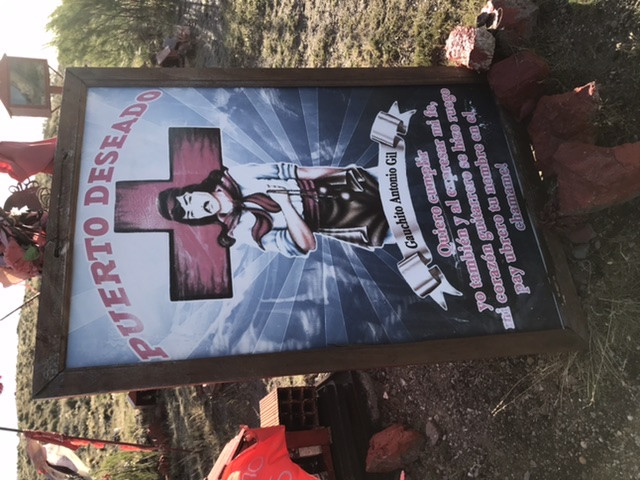

Lynnette and I now have a plastic Gauchito Gil for our dashboard.

After re-stacking with groceries, doing laundry and getting the truck repaired in Puerto Deseado, Lynnette and I decided to run across the width of Patagonia on Ruta 43 and check out a village near the Chilean border named Los Antiguos. Los Antiguos was described as a garden spot, and famous for growing cherries. We figured the drive would be a leisurely two day trip.

Our last stop was the grocery store, where we ran into two Overland Trucks of the Apocalypse sporting Swiss registrations. Each truck was plastered with stickers of past adventures in north Africa. While we are certain those trucks are the ticket for rural Africa, Asia & Australia we haven’t really seen where they would be much use here in Patagonian South America; access to public lands proscribes remaining on marked roads and most land here is private. We don’t know who would want these ripping up their estancia. The style of truck also looks alien and intimidating, not directly relatable to the common person (when I posted this photo on Instagram a friend asked if I had truck envy. No, Lynnette and I both agree: It ain’t the size of the truck, it’s what you do with it).

Feeling quite secure with our little -but-mighty-truck, Tuco, We headed-out of Puerto Deseado westward, intending to score a campsite halfway across Patagonia on Ruta 43. There were two towns named Pica Truncata and Las Heras. There had to be a campsite somewhere along the way. There was not. What we did see was an industrial wasteland of churning oil wells, posted side roads busy with ingress and egress of service trucks and trash, everywhere. We will never forget passing by the town of Pica Truncata which was surrounded for several Km in all directions with a white coating of flapping plastic wrap, plastic bags and plastic containers of all sorts as the changing winds blew it out of the landfill and redistributed it. The stuff was blowing through the town, lodging and clinging everywhere and to everything. We were literally in shock observing it. We regret not getting a photo of this environmental horror. We also regret not getting a photo of the recycling center for town residents to sort their household trash placed smack-dab in the middle of where the highway passed through town. What Irony.

The sun was rapidly setting as we continue to westward. We attempted to set up camp at a gravel pit that offered shelter from the wind and privacy from view. It was,after all, Saturday night; things should be quiet. No dice. Within minutes two giant dump trucks rattled right past us. Onward we went.

We passed by a small restaurant tucked into a stand of trees in the middle of nowhere that advertised food, day picnicking & WiFi. Walking in, I found the host, dressed in his finest gaucho attire. Coals were glowing on the grill and the tables were empty. It was 9 o’clock at night and it looked like nobody had been there. “May we camp?” I asked. He turned to his wife and repeated my question. “No, impossible.” Was his reply. Nothing is impossible, buddy, I thought, unless you proclaim it so. Good luck with your venture.

The oil fields were behind us and now we were running an endless string of fence lines leading to the setting sun. We felt doomed to travel the entire width of Argentine Patagonia to Perito Moreno then sleep in a gas station parking lot when a small tent icon appeared on the GPS. “Spot near estancia gate” it advertised, “Near a cattle guard. It offers a little protection from the wind.” Done deal. We slept to the wind shaking our camper through the night.

The next day we wound our way into Perito Moreno to a fuel station on 40 we’d visited a couple weeks back on the way south. We stocked on fuel, munched a couple empanadas and checked up on the Wi-Fi. Most Argentine fuel stations offer a small café within them. As we munched our empanadas at the rear of the cafe we saw a large, locked room, sterile-white with nothing in it but a restored late 1950s Dodge Imperial and a couple of period easy chairs in a corner, which, we assumed, would be used by privileged admirers.

Running along the edge of Lago Buenos Aires numerous tent icons begin popping up on the GPS. The wind was howling. All of the sites were exposed and none looked appealing save one estancia offering cabins and camping. The gate was open as we passed so, we decided we would see what was available near town before committing.

Los Antiguos is a delightful little town. We walked the streets to find most shops closed. There appeared to be signs of the upcoming Cherry Festival and street vendor booths were set up & ready to receive occupants.

We did see one late 1970s Volkswagen bus with a Westphalia popup sitting at the main square. The van had markings which announced it’s intention to reach Alaska. On our first pass walking the vans curtains were drawn but as we came around again driving our truck we saw the vans doors open and the occupants standing beside it.

It was a young couple, Jeremias y Josephine, and their two dogs. We introduced ourselves, saying after seeing their proclamation we had to meet them. We exchanged stories and photos then bade one another farewell.

As siesta time quit the usual symphony of cars-sans-muffler, motorbikes and loud music promoted by the youth in every Argentine town began. We decided our best option was to snub the in-town campgrounds to visit the estancia several kilometers back along the lake. While making our way, the wind was at our backs. Our camper acted as a sail, allowing us to go 100 kph with little effort.

Arriving at the estancia, we found the gate to be locked. We then checked our other options leading back to town and found a nearby National Park site along the lake called Estancia La Ascencion.

Estancia La Ascencion is a former sheep estancia going back to about 1915, and it’s in immaculate period condition.

There is a materia, or mate house, where the estancia help would gather to drink mate.

The sheep shearing barn is replete with worn wood floors & fences, along with an old canvas pulley system for running the mechanical sheep shears.

The fields throughout the estancia in the hectares near the lake are sectioned off by willows, poplars and other mature trees.

This is the only national Park in Argentina we found that offered overnight camping. We drove to the campsite nearest the lake and found several beautiful quincho’s set up and ready. Dead wood was available everywhere for fuel.

A large, extended Argentine family was finishing their Sunday afternoon asado as we pulled in. As I was walking past with an armful of firewood the father came out to greet me. ”Hola.” ”Where are you from?” “Where are you going?” “That’s a very interesting camper!” The usual questions and comments came in Spanish. Slowly, his children and grandchildren came out and begin to gather around me as I told our story in my halting, simple Spanish.

One of the grandchildren came through the circle and offered me a cherry from a basket. I took one and thanked her, then told her my wife loves cherries and would she please give her one?

Lynnette was thrilled to receive a cherry from the little girl, who was looking curiously into the camper.

Before long, the entire family; four generations; had abandoned their asado and were gathered around the back of the camper, asking us questions.

Lynnette invited them in for a tour and, one by one, they all came inside to see how we were living for four months. Using our simple Spanish and iPhone translator, we answered their rapidfire questions as best we could.

The little children wanted to know about the United States. A little boy asked me “is chocolate expensive in the United States?” We said “No. Do you like chocolate?” Wherein Lynnette brought-out several chocolate bars which we gave to the children and opened & shared with the adults.

One of the sons, the father of the little girl, then came through the crowd with an offering: a miniature statue of Gauchito Gil, which he said would keep us safe in our journey. We were dumbstruck.

Gauchito Gil is a folk saint with wide popularity in Argentina and to lesser extent in portions of Chile, Brazil and Paraguay. We have been seeing the red shrines, waving flags and statues of the Gil cult across our entire trip in Argentina. The legend goes “Gauchito” Antonio Mamerto Gil Nunez was born in Corrientes in the 1840’s and grew up as a farm hand. After repeated scrapes of injustice with the wealthy class, the law and two stints of conscription in the civil wars he deserted to become an outlaw. He then made a name for himself by robbing from the rich and giving to those suffering under extreme poverty. He reportedly had mystical powers of healing and hypnosis. When he was finally caught, he was tortured and sentenced to execution on January 8, 1878. Just before his sentence was carried out, Gil told the sergeant-in-command that a letter of commutation for Gil and news that the sergeants son was dying awaited the sergeant at the command post. Gil said that the child would be spared if the sergeant prayed for Gils soul. The Sergeant dismissed Gils presentment and slit his throat

When the sergeant returned to his post, he found a soldier there with a letter of pardon for Gil. The letter also said that the sergeant's son was very ill and on the brink of dying. Frightened, the sergeant prayed to Gauchito Gil for his son to be saved. The next day, his son was inexplicably cured; Gauchito Gil had healed the son of his murderer. Very grateful, the sergeant gave Gil's body a proper burial, and in his honor built a shrine in the form of a red cross. Moreover, he tried to let everybody know about the miracle. Now, the site in Corrientes Province is a shrine filled with tributes and exhortations of thanks for the many, many people who claim miracles from Gauchito Gil. Over 200,000 people reportedly make a pilgrimage to the shrine annually to request favors. The date of Gils death, January 8, is marked by a major festival in Corrientes that includes feasts, games and a huge procession from the nearby cathedral to his grave

Gauchito Gil is not recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church though many Argentines, both devotees and church leaders, have been promoting him for canonization.

Shrines to Gil are everywhere in Argentina. Some are simple, doghouse-sized red huts with a couple flags, others are quite grand.

We saw one recently in Puerto Deseado that had several huts, a plethora of flags and signs along with two life-sized figurines of Gil.

With began to inspect the shrines closer to see what people are leaving as offerings of thanks. Commonly, we see boxes, bottles, and glasses of wine, cigarettes and candles. We see lots of handwritten notes tucked within the shrines.

As we fill the road miles with contemplation, we wonder: What causes someone to declare a shrine should be placed at a certain location? Why do some shrines expand? Why do some fall into disuse? Those answers are yet to be revealed.

We’d figured, several days before, at the least, we would do our best to find a statue of Gil to take home with us as a remembrance of this frequent icon of the trip. We had been scouring the towns looking for some type of store that could provide. Only hours before, with a laugh, we had commented it would be fun to at least get a dashboard Gil. Then, shortly thereafter, to our shocked amazement, one gets presented to us. We are calling it a little miracle of it’s own.

Through sobs, Lynnette accepted the heartfelt gift from the modest family that had reached-out to meet us, had come to like us and had given something sacred of them, to us. They immediately ran to their car and returned with a Gauchito Gil flag, and a Gauchito Gil coffee cup as additional gifts.

The father remarked that he will never forget us and that we will always be remembered in their hearts. With much emotion we all hugged, kissed then bade one-another farewell. They continued waving as their cars slowly crept out of sight.

While the plastic, dashboard Saints themselves do not have the power to protect us, nor part traffic, they remind us to be grateful, and humble. They can remind us to be courageous as we go forward into the unknown. They might keep us mindful and considerate of others around us; we then alter our behavior accordingly and get positive results.

In a recent town we had splurged and bought a complete mate kit. Thus, we had an extra cup and straw. As we found the next Gauchito Gil shrine we considered that, perhaps, he’d had enough wine & cigarettes and, being a gaucho, would appreciate a hot cup of mate. We filled our extra mate cup with fresh Yerba, a straw and hot water then placed it into the shrine.