Frontiers

The Oxford Dictionary defines a frontier as “a line or border between two countries”. By the same source a frontier is also considered to be “the extreme limit of understanding or achievement in a particular area”. While crossing between Argentina and Chile, we found the absolute of the first definition, and the irony in the second.

Late December, while we were approaching the Argentine/Chilean frontier at the south of the continent where it meets the island of Tierra del Fuego, we were contacted by Orvis Travel. The folks at Orvis Travel, long time friends, were in need of a host to represent them at Magic Waters Patagonia Lodge in Chile two weeks hence. The owners of Magic Waters are also friends. It didn’t take long for us to consider the question then say yes. We weren’t that interested in jostling with the mad-throngs of tourists at Ushuia, the southernmost city on the planet, anyway.

We had a fine, leisurely time making our way up to eastern coast of Argentina. Suspecting we may have trouble trying to get our truck across the Chilean/Argentine frontier, we made sure we left a couple extra days of buffer in case there were issues in the attempt of getting across.

In an earlier story we described how we were put on blast by the Argentine customs while returning from Chile. We were told our truck could not leave Argentina because it was illegal for a person residing outside of Argentina who owned a vehicle in Argentina to remove vehicle from Argentina. We thought that to be very odd, because of earlier research told us nothing of the kind. Just the same, we did not wish to take any chances of having difficulties at the last minute.

Our trip across the width of Argentina was through an oil field region offering few opportunities for camping nor notable sites of interest so we arrived to the Argentine border city of Los Antiguos a couple days early. We had a delightful stay at a local National Park as we ate-down our provisions (both countries prohibit the import of fresh meats, cheeses, fruits and vegetables).

We made our way to the frontier at the Chilean town of Chile Chico, our paperwork in hand and confident of a successful crossing. The processing format is actually quite efficient. There are four steps to a successful crossing:

First, visit the immigration representative of the country departing to make sure you, personally, are eligible to depart and get your passport stamped.

Second, visit the customs representative of the departing country to process the departure of your vehicle and, potentially, its contents.

Third, visit the customs representative of the arriving country to get a permit for your vehicle or, if it’s a vehicle registered to that country, validation of that vehicle’s ability to enter. Your vehicle is then subject to a search for the various foods described above or other potentially prohibited or taxable contents.

Fourth, visit the immigration representative of the arriving country to make sure you, personally, are eligible to enter and have your passport stamped.

All four of these agencies are neatly lined up in a row within one room at the busier frontiers between Chile and Argentina. Chile Chico is one of the busier frontiers. Chile Chico is the point where overland, bus, motorcycle & bicycle tourists come out of Chile traveling the entire length of the Carretera Austral on their way to the southernmost parks of Patagonia then ultimately the Tierra del Fuegan cities of Punta Arenas, in Chile, or Ushuaia, in Argentina.

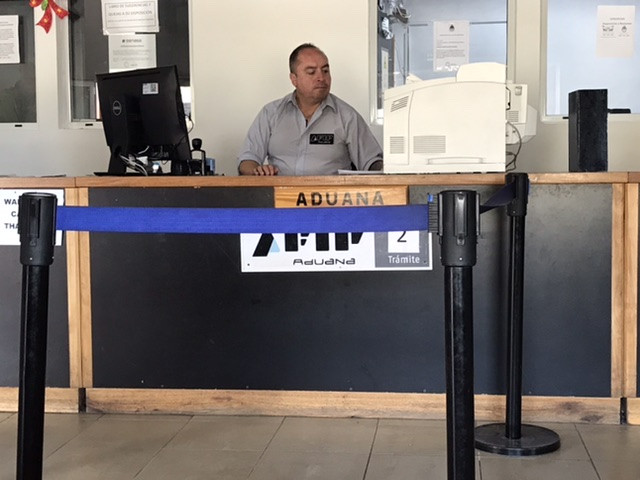

Our passport was stamped-out of Argentina quickly. We then made our way to the Argentine Aduana, or customs, where a man sat with a pinched expression upon his face.

“Where is your rental agreement?“ was his first question upon receiving our paperwork .

“There is no rental agreement. We own the vehicle.“

“Do you live in Argentina?”

“No.”

“Then how can you own an Argentine vehicle?”

“I use the address of my friend”

“The addresses of your passport and registration do not match. You cannot take this vehicle out of Argentina!”

A drawn-out drama then ensued where I insisted we could take the truck out of Argentina because we had all the paperwork. Mr. Aduana then called a supervisor who insisted we could not because our paperwork listed an address different than our passports. I called our friend, Carlos Sanchez, who got on the phone with Mr. Aduana and, after a heated exchange, the end result was: Thumbs-down. The truck was not going to leave Argentina.

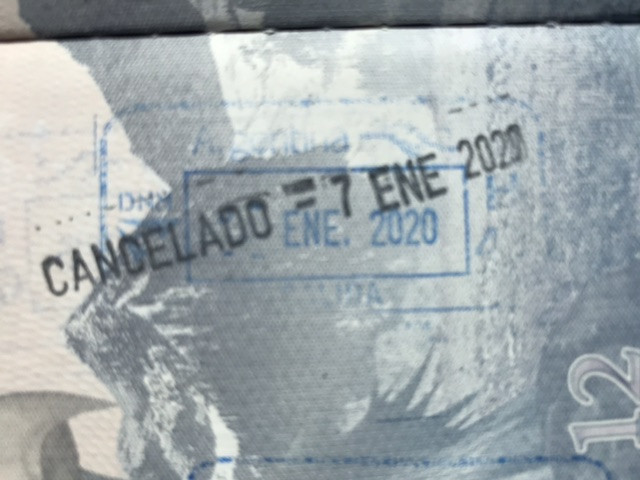

We then were handed our passports and pile of papers back. It was then I realized that Lynnette and I were people without a country. We explained the situation to the Chilean immigration agent who, gracefully, stamped our passports over the Argentine exit stamp as ‘cancelled’ then handed them back to their Argentine counterparts.

As I stepped forward to claim our passports Mr. Aduana was loudly telling a crowd of gathered Argentine agents the story of his Red Tape Victory as the agents all shot us sheepish glances. A kindly Argentine agent handed us back our passports with the nod and smile. “Gracias!”, I said, “Bienvenidos a Argentina!” (Welcome to Argentina) I added in a sarcastic vein. The assembled crowd of agents looked up and gave us apologetic smiles. Mr. Aduana never gave us another look. He spun on his heels and left the room. He had reached his extreme limit of understanding & achievement in this particular area.

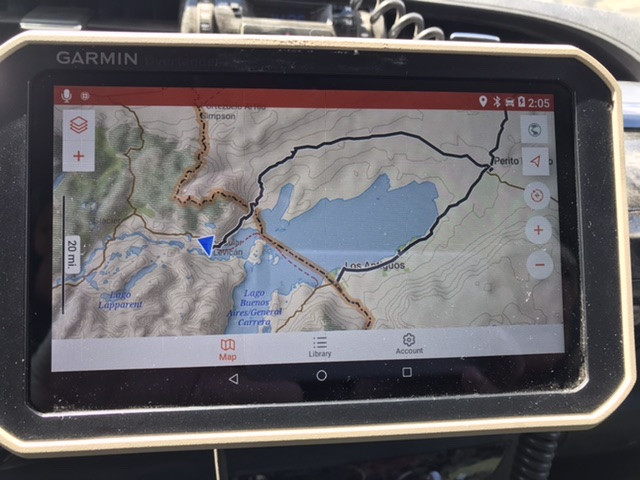

Suddenly, we realized we had a problem to solve. Fortunately, we had several days to solve it. We briefly considered the extreme solution of leaving the truck in an Argentine town and taking a bus into Chile. That was one possibility and a card we were not ready to play. The other was to keep shopping Argentine frontier crossings until we found one that was cooperative. The day was still early. We looked at the map and determined there was another crossing within sight of where we stood, in the mountains on the other side of the gigantic Lago Buenos Aires. We entered the destination into the GPS.

While it was only 52 km to reach this frontier post, the road was in a horrible condition of washboard, loose gravel rows, large rocks and potholes that it took us three hours of moving at a crawl-pace to reach it. In places the road was so unbearable that vehicles previously passing this route were actually driving in the ditch to find the smoothest path. We tried the same strategy and it offered little advantage. The only traffic we encountered on this road were two adventure motorcyclists hanging onto their bikes for dear life. We waved at them. One cyclist took his hand off the handle bar for a brief second to wave back. It almost cost him a crash.

The road kept narrowing and becoming more sinuous. We were doubting our path, because the road had become just that, when we finally came to the Argentine frontier post.

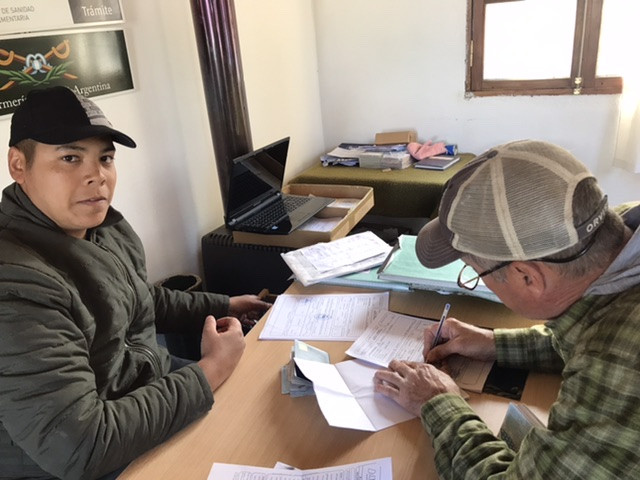

The frontier post looked like something out of the movie Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid. A collection of tiny buildings made of adobe flanked a gate made of pipe & balanced by a concrete counterweight. The gate looked to have been painted with white and red paint about 5000 times. Horses were corralled within some nearby trees and a friendly dog was tied to a leash, barking & begging for attention. As we scratched the dog the Argentine agent came out of a building and invited us into his office.

The agent had no computer. Everything was done by using an old, handwritten logbook and our exit permit was handwritten making carbon paper copies. I had just sucked down an entire thermos of mate and my nerves were jumpy. Lynnette and I were so paranoid of being rejected. I folded our passports over & past the page that showed the cancelled attempt to leave Argentina earlier that day. The agent excused himself from the room three times. We squirmed in our chairs. (what if he’s calling the same supervisor Mr. Aduana called!?). We tried hard to appear like we were NOT smuggling drugs or trafficking humans. The agent eventually finished the paperwork, handed us our passports & permit, took a quick look at the truck & its contents, then cheerfully opened the gate. He told us the Chilean port of entry was 24 km down the road and wished us well. We were in Chile.

We were also elated and felt like we’d just robbed a bank.

After one last switchback road incline that was no better than a goat trail, we came to a livestock fence with a wind-battered sign that said ‘Welcome to Chile’ in Spanish. As we crossed through the fence we were treated to a one lane, smooth road made of paving bricks bordered with a concrete edge.

The road should have been painted yellow. It was like something out of the Wizard of Oz, being on this winding mountain road made of bricks that took us through astonishingly beautiful canyons while the deep, glacial blue of the lake, now named Lago General Carrera in Chile, shone steady on our left as the sun set before us.

While at a delightful Chilean cafe that had a couple house cats indoors, we reflected back to our border crossing and realized the one, crucial question from the Argentine frontier guard we’d answered differently:

“Do you live in Argentina?”

“Yes.”

No lie.